Continuous Delivery Using Maven

I’m currently working on a continuous delivery system where I work, so I thought I would write something up about what I’m doing. The continuous delivery system, in a nutshell, looks a bit like this:

I started out with a bit of a carte blanche with regards to what tools to use, but here’s a list of what was already in use, in one form or another, when I started my adventure:

- Ant (the main build tool)

- Maven (used for dependency management)

- CruiseControl

- CruiseControl.Net

- Go

- Monit

- JUnit

- js-test-driver

- Selenium

- Artifactory

- Perforce

The decision of which of these tools to use for my system was influenced by a number of factors. Firstly I’ll explain why I decided to use Maven as the build tool (shock!!).

I’m a big fan of Ant, I’d usually choose it (or probably Gradle now) over Maven any day of the week, but there was already an existing Ant build system in place, which had grown a bit monolithic (that’s my polite way of saying it was a huge mess), so I didn’t want to go there! And besides, the first project that would be going into the new continuous delivery system was a simple Java project – way too straightforward to justify rewriting the whole ant system from scratch and improving it, so I went for Maven. Furthermore, since the project was (from a build perspective) fairly straightforward, I thought Maven could handle it without too much bother. I’ve used Maven before, so I’ve had my run-ins with it, and I know how hard it can be if you want to do anything outside of “The Maven Way”. But, as I said, the project I was working on seemed pretty simple so Maven got the nod.

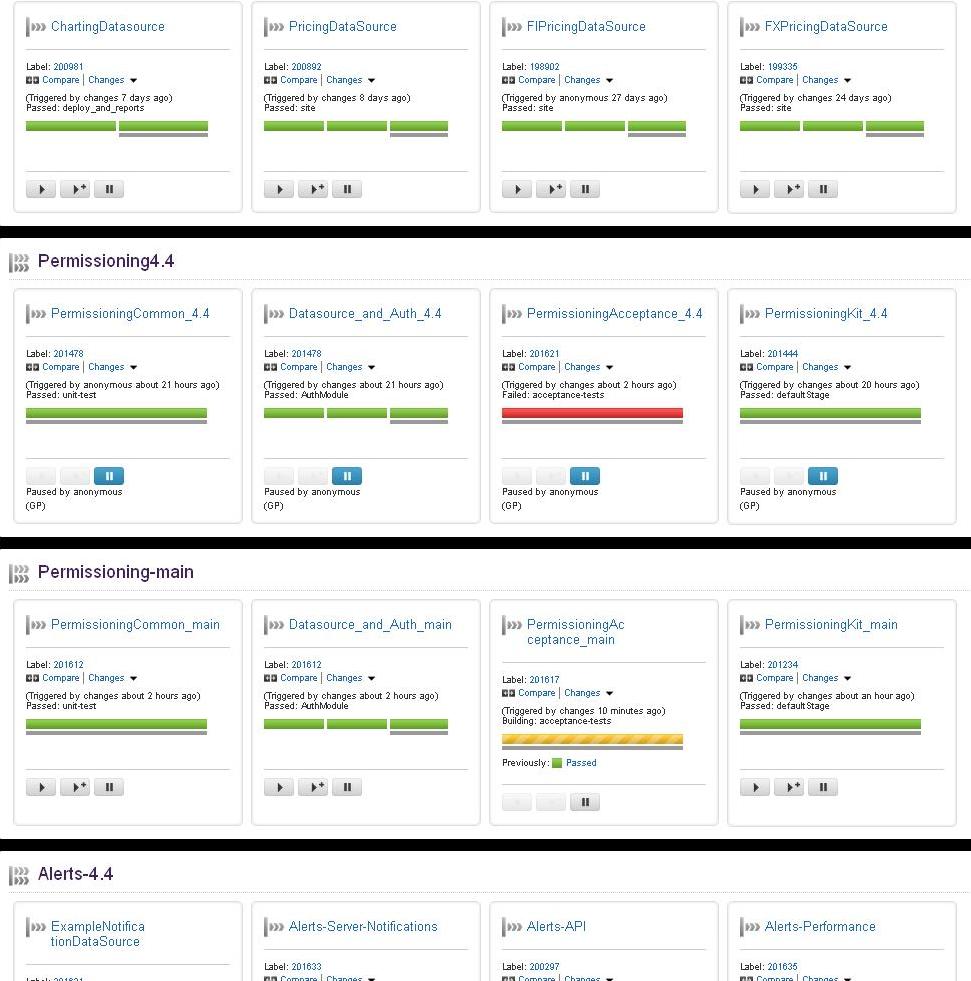

GO was the latest and greatest C.I. server in use, and the CruiseControl systems were a bit of a handful already, so I went for GO (also I’d never used it before so I thought that would be cool, and it’s from Thoughtworks Studios, so I thought it might be pretty good). I particularly liked the pipeline feature it has, and the way it manages each of its own agents. A colleague of mine, Andy Berry, had already done quite a bit of work on the GO C.I. system, so there was already something to start from. I would have gone for Jenkins had there not already been a considerable investment in GO by the company prior to my arrival.

I decided to use Artifactory as the artifact repository manager, simply because there was already an instance installed, and it was sort-of already setup. The existing build system didn’t really use it, as most artifacts/dependencies were served from network shares. I would have considered Nexus if Artifactory wasn’t already installed.

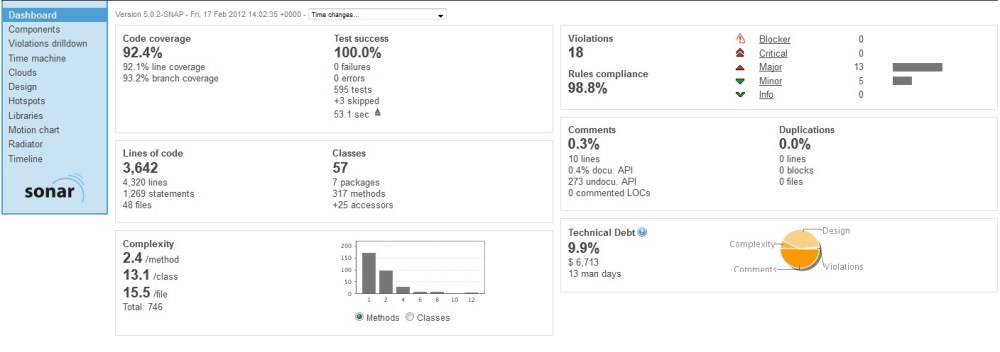

I setup Sonar to act as a build analysis/reporting tool, because we were starting with a Java project. I really like what Sonar does, I think the information it presents can be used very effectively. Most of all I just like the way in which it delivers the information. The Maven site plugin can produce pretty much all of the information that Sonar does, but I think the way Sonar presents the information is far superior – more on this later.

Perforce was the incumbent source control system, and so it was a no-brainer to carry on with that. In fact, changing the SC system wasn’t ever in question. That said, I would have chosen Subversion if this was an option, just because it’s so utterly freeeeeeee!!!

That was about it for the tools I wanted to use. It was up to the rest of the project team to determine which tools to use for testing and developing. All that I needed for the system I was setting up was a distinction between the Unit Tests, Acceptance Tests and Integration Tests. In the end, the team went with Junit, Mockito and a couple of in-house apps to take care of the testing.

The Maven Build, and the Joys of the Release Plugin!

The idea behind my Continuous Delivery system was this:

- Every check-in runs a load of unit tests

- If they pass it runs a load of acceptance tests

- If they pass we run more tests – Integration, scenario and performance tests

- If they all pass we run a bunch of static analysis and produce pretty reports and eventually deploy the candidate to a “Release Candidate” repository where QA and other like-minded people can look at it, prod it, and eventually give it a seal of approval.

This is the basic outline of a build pipeline:

Maven isn’t exactly fantastic at fitting in to the pipeline process. For starters we’re running multiple test phases, and Maven follows a “lifecycle” process, meaning that every time you call a particular pipeline phase, it runs all the preceding phases again. Our pipeline needs to run the maven Surefire plugin twice, because that’s the plugin we use to execute our different tests. The first time we run it, we want to execute all the unit tests. The second time we run it we want to execute the acceptance tests – but we don’t want it to run the unit tests again, obviously.

Maven isn’t exactly fantastic at fitting in to the pipeline process. For starters we’re running multiple test phases, and Maven follows a “lifecycle” process, meaning that every time you call a particular pipeline phase, it runs all the preceding phases again. Our pipeline needs to run the maven Surefire plugin twice, because that’s the plugin we use to execute our different tests. The first time we run it, we want to execute all the unit tests. The second time we run it we want to execute the acceptance tests – but we don’t want it to run the unit tests again, obviously.

You probably need some familiarity with the maven build lifecycle at this point, because we’re going to be binding the Surefire plugin to two different phases of the maven lifecycle so that we can run it twice and have it run different tests each time. Here is the maven lifecycle, (for a more detailed description check out the Maven’s own lifecycle page)

Clean Lifecycle

- pre-clean

- clean

- post-clean

Default Lifecycle

- validate

- initialize

- generate-sources

- process-sources

- generate-resources

- process-resources

- compile

- process-classes

- generate-test-sources

- process-test-sources

- generate-test-resources

- process-test-resources

- test-compile

- process-test-classes

- test

- prepare-package

- package

- pre-integration-test

- integration-test

- post-integration-test

- verify

- install

- deploy

Site Lifecycle

- pre-site

- site

- post-site

- site-deploy

So, we want to bind our Surefire plugin to both the test phase to execute the UTs, and the integration-test phase to run the ATs, like this:

<plugin>

<!-- Separates the unit tests from the integration tests. -->

<groupId>org.apache.maven.plugins</groupId>

<artifactId>maven-surefire-plugin</artifactId>

<configuration>

-Xms256m -Xmx512m

<skip>true</skip>

</configuration>

<executions>

<execution>

<id>unit-tests</id>

<phase>test</phase>

<goals>

<goal>test</goal>

</goals>

<configuration>

<testClassesDirectory>

target/test-classes

</testClassesDirectory>

<skip>false</skip>

<includes>

<include>**/*Test.java</include>

</includes>

<excludes>

<exclude>**/acceptance/*.java</exclude>

<exclude>**/benchmark/*.java</exclude>

<include>**/requestResponses/*Test.java</exclude>

</excludes>

</configuration>

</execution>

<execution>

<id>acceptance-tests</id>

<phase>integration-test</phase>

<goals>

<goal>test</goal>

</goals>

<configuration>

<testClassesDirectory>

target/test-classes

</testClassesDirectory>

<skip>false</skip>

<includes>

<include>**/acceptance/*.java</include>

<include>**/benchmark/*.java</include>

<include>**/requestResponses/*Test.java</exclude>

</includes>

</configuration>

</execution>

</executions>

</plugin>

Now in the first stage of our pipeline, which polls Perforce for changes, triggers a build and runs the unit tests, we simply call:

mvn clean test

This will run the surefire test phase of the maven lifecycle. As you can see from the Surefire plugin configuration above, during the “test” phase execution of Surefire (i.e. this time we run it) it’ll run all of the tests except for the acceptance tests – these are explicitly excluded from the execution in the “excludes” section. The other thing we want to do in this phase is quickly check the unit test coverage for our project, and maybe make the build fail if the test coverage is below a certain level. To do this we use the cobertura plugin, and configure it as follows:

<plugin>

<groupId>org.codehaus.mojo</groupId>

<artifactId>cobertura-maven-plugin</artifactId>

<version>2.4</version>

<configuration>

<instrumentation>

<excludes><!-- this is why this isn't in the parent -->

<exclude>**/acceptance/*.class</exclude>

<exclude>**/benchmark/*.class</exclude>

<exclude>**/requestResponses/*.class</exclude>

</excludes>

</instrumentation>

<check>

<haltOnFailure>true</haltOnFailure>

<branchRate>80</branchRate>

<lineRate>80</lineRate>

<packageLineRate>80</packageLineRate>

<packageBranchRate>80</packageBranchRate>

<totalBranchRate>80</totalBranchRate>

<totalLineRate>80</totalLineRate>

</check>

<formats>

<format>html</format>

<format>xml</format>

</formats>

</configuration>

<executions>

<execution>

<phase>test</phase>

<goals>

<goal>clean</goal>

<goal>check</goal>

</goals>

</execution>

</executions>

</plugin>

To get the cobertura plugin to execute, we need to call “mvn cobertura:cobertura”, or run the maven “verify” phase by calling “mvn verify”, because the cobertura plugin by default binds to the verify lifecycle phase. But if we delve a little deeper into what this actually does, we see that it actually runs the whole test phase all over again, and of course the integration-test phase too, because they precede the verify phase, and cobertura:cobertura actually invokes execution of the test phase before executing itself. So what I’ve done is to change the lifecycle phase that cobertura binds to, as you can see above. I’ve made it bind to the test phase only, so that it only executes when the unit tests run. A consequence of this is that we can now change the maven command we run, to something like this:

mvn clean cobertura:cobertura

This will run the Unit Tests implicitly and also check the coverage!

In the second stage of the pipeline, which runs the acceptance tests, we can call:

mvn clean integration-test

This will again run the Surefire plugin, but this time it will run through the test phase (thus executing the unit tests again) and then execute the integration-test phase, which actually runs our acceptance tests.

You’ll notice that we’ve run the unit tests twice now, and this is a problem. Or is it? Well actually no it isn’t, not for me anyway. One of the reasons why the pipeline is broken down into sections is to allow us to separate different tasks according to their purpose. My Unit Tests are meant to run very quickly (less than 3 minutes ideally, they actually take 15 seconds on this particular project) so that if they fail, I know about it asap, and I don’t have to wait around for a lifetime before I can either continue checking in, or start fixing the failed tests. So my unit test pipeline phase needs to be quick, but what difference does an extra few seconds mean for my Acceptance Tests? Not too much to be honest, so I’m actually not too fussed about the unit tests running for a second time. If it was a problem, I would of course have to somehow skip the unit tests, but only in the test phase on the second run. This is doable, but not very easy. The best way I’ve thought of is to exclude the tests using SkipTests, which actually just skips the execution of the surefire plugin, and then run your acceptance tests using a different plugin (the Antrun plugin for instance).

The next thing we want to do is create a built artifact (a jar or zip for example) and upload it to our artifact repository. We’ll use 5 artifact repositories in our continuous delivery system, these are:

- A cached copy of the maven central repo

- A C.I. repository where all builds go

- A Release Candidate (RC) repository where all builds under QA go

- A Release repository where all builds which have passed QA go

- A Downloads repository, from where the downloads to customers are actually served

Once our build has passed all the automated test phases it gets deployed to the C.I. repository. This is done by configuring the C.I. repository in the maven pom file as follows:

<distributionManagement>

<repository>

<id>CI-repo</id>

<url>http://artifactory.mycompany.com/ci-repo</url>

</repository>

</distributionManagement>

and calling:

mvn clean deploy

Now, since Maven follows the lifecycle pattern, it’ll rerun the tests again, and we don’t want to do all that, we just want to deploy the artifacts. In fact, there’s no reason why we shouldn’t just deploy the artifact straight after the Acceptance Test stage is completed, so that’s what exactly what we’ll do. This means we need to go back and change our maven command for our Acceptance Test stage as follows:

mvn clean deploy

This does the same as it did before, because the integration-test phase is implicit and is executed on the way to reaching the “deploy” phase as part of the maven lifecycle, but of course it does more than it did before, it actually deploys the artifact to the C.I. repository.

One thing that is worth noting here is that I’m not using the maven release plugin, and that’s because it’s not very well suited to continuous delivery, as I’ve noted here. The main problem is that the release plugin will increment the build number in the pom and check it in, which will in turn kick off another build, and if every build is doing this, then you’ll have an infinitely building loop. Maven declares builds as either a “release build” which uses the release plugin, or a SNAPSHOT build, which is basically anything else. But I want to create releases out of SNAPSHOT builds, but I don’t want them to be called SNAPSHOT builds, because they’re releases! So what I need to do is simply remove the word SNAPSHOT from my pom. Get rid of it entirely. This will now build a normal “snapshot” build, but not add the SNAPSHOT label, and since we’re not running the release plugin, that’s fine (WARNING: if you try removing the word snapshot from your pom and then try to run a release build using the release plugin, it’ll fail).

Ok, let’s briefly catch up with what our system can now do:

- We’ve got a build pipeline with 2 stages

- It’s executed every time code is checked-in

- Unit tests are executed in the first stage

- Code coverage is checked, also in the first stage

- The second stage runs the acceptance tests

- The jar/zip is built and deployed to our ci repo, this also in the second stage of our pipeline

So we have a jar, and it’s in our “ci” repo, and we have a code coverage report. But where’s the rest of our static analysis? The build should report a lot more than just the code coverage. What about coding styles & standards, rules violations, potential defect hot spots, copy and pasted code etc and so forth??? Thankfully, there’s a great tool which collects all this information for us, and it’s called Sonar.

I won’t go into detail about how to setup and install Sonar, because I’ve already detailed it here.

Installing Sonar is very simple, and to get your builds to produce Sonar reports is as simple as adding a small amount of configuration to your pom, and adding the Sonar plugin to you plugin section. To produce the Sonar reports for your project, you can simply run:

mvn sonar:sonar

So that’s exactly what we’ll do in the next section of our build pipeline.

So we now have 3 pipeline sections and were producing Sonar reports with every build. The Sonar reports look something like this:

As you can see, Sonar produces a wealth of useful information which we can pour over and discuss in our daily stand-ups. As a rule we try to fix any “critical” rule violations, and keep the unit test coverage percentage up in the 90s (where appropriate). Some people might argue that unit test coverage isn’t a valuable metric, but bear in mind that Sonar allows you to exclude certain files and directories from your analysis, so that you’re only measuring the unit test coverage of the code you want to have covered by unit tests. For me, this makes it a valuable metric.

Moving on from Sonar now, we get to the next stage of my pipeline, and here I’m going to run some Integration Tests (finally!!). The ITs have a much wider scope than the Unit Test, and they also have greater requirements, in that we need an Integration Test Environment to run them in. I’m going to use Ant to control this phase of the pipeline, because it gives me more control than Maven does, and I need to do a couple of funky things, namely:

- Provision an environment

- Deploy all the components I need to test with

- Get my newly built artifact from the ci repository in Artifactory

- Deploy it to my IT environment

- Kick of the tests

The Ant script is fairly straightforward, but I’ll just mention that getting our artifact from Artifactory is as simple as using Ant’s own “get” task (you don’t need to use Ivy juts to do this):

<get src=”${artifactory.url}/${repo.name}/${namespace}/${jarname}-${version}” dest=”${temp.dir}/${jarname}-${version}” />

The Integration Test stage takes a little longer than the previous stages, and so to speed things up we can run this stage in parallel with the previous stage. Go allows us to do this by setting up 2 jobs in one pipeline stage. Our Sonar stage now changes to “Reports and ITs”, and includes 2 jobs:

<jobs>

<job name="sonar">

<tasks>

<exec command="mvn" args="sonar:sonar" workingdir="JavaDevelopment" />

</tasks>

<resources>

<resource>windows</resource>

</resources>

</job>

<job name="ITs">

<tasks>

<ant buildfile="run_ITs.xml" target="build" workingdir="JavaDevelopment" />

</tasks>

<resources>

<resource>windows</resource>

</resources>

</job>

</jobs>

Once this phase completes successfully, we know we’ve got a half decent looking build! At this point I’m going to throw a bit of a spanner into the works. The QA team want to perform some manual exploratory tests on the build. Good idea! But how does that fit in with our Continuous Delivery model? Well, what I did was to create a separate “Release Candidate” (RC) repository, also known as a QA repo. Builds that pass the IT stage get promoted to the RC repo, and from there the QA team can take them and do their exploratory testing.

Does this stop us from practicing “Continuous Delivery”? Well, not really. In my opinion, Continuous Delivery is more about making sure that every build creates a potentially releasable artifact, rather that making every build actually deploy an artifact to production – that’s Continuous Deployment.

Our final stage in the deployment pipeline is to deploy our build to a performance test environment, and execute some load tests. Once this stage completes we deploy our build to the Release Repository, as it’s all signed off and ready to handover to customers. At this point there’s a manual decision gate, which in reality is a button in my CI system. At this point, only the product owner or some such responsible person, can decide whether or not to actually release this build into the wild. They may decide not to, simply because they don’t feel that the changes included in this build are particularly worth deploying. On the other hand, they may decide to release it, and to do this they simply click the button. What does the button do? Well, it simply copies the build to the “downloads” repository, from where a link is served and sent to customers, informing them that a new release is available – that’s just the way things are done here. In a hosted environment (like a web-based company), this button-press could initiate the deploy script to deploy this build to the production environment.

A Word on Version Numbers

This system is actually dependant on each build producing a unique artifact. If a code change is checked in, the resultant build must be uniquely identifiable, so that when we come to release it, we know we’re releasing theexact same build that has gone through the whole pipeline, not some older previous build. To do this, we need to version each build with a unique number. The CI system is very useful for doing this. In Go, as with most other CI systems, you can retrieve a unique “counter” for your build, which is incremented every time there’s a build. No two builds of the same name can have the same counter. So we could add this unique number to our artifact’s version, something like this (let’s say the counter is 33, meaning this is the 33rd build):

myproject.jar-1.0.33

This is good, but it doesn’t tell us much, apart from that this is the 33rd build of “myproject”. A more meaningful version number is the source control revision number, which relates to the code commit which kicked off the build. This is extremely useful. From this we can cross reference every build to the code in our source control system, and this saves us from having to “tag” the source code with every build. I can access the source control revision number via my CI system, because Go sets it as an environment variable at build time, so I simply pass it to my build script in my CI system’s xml, like this:

cobertura:cobertura -Dp4.revision=${env.GO_PIPELINE_LABEL}

-Dbuild.counter=${env.GO_PIPELINE_COUNTER"

p4.revision and build.counter are used in the maven build script, where I set the version number:

<groupId>com.mycompany</groupId>

<artifactId>myproject</artifactId>

<packaging>jar</packaging>

<version>${main.version}-${build.number}-${build.counter}</version>

<name>myproject</name><properties>

<build.number>${p4.revision}</build.number>

<major.version>1</major.version>

<minor.version>0</minor.version>

<patch.version>0</patch.version>

<main.version>${major.version}.${minor.version}.${patch.version}</main.version>

</properties>

If my Perforce check-in number was 1234, then this build, for example, will produce:

myproject.jar-1.0.0-1234-33

And that just about covers it. I hope this is useful to some people, especially those who are using Maven and are struggling with the release plugin!