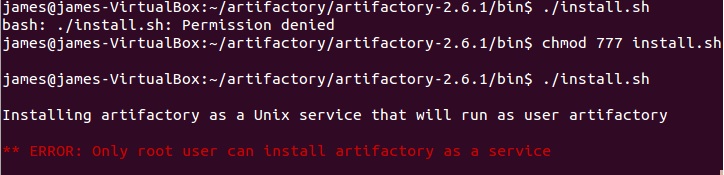

Agile ITOps: Day 1

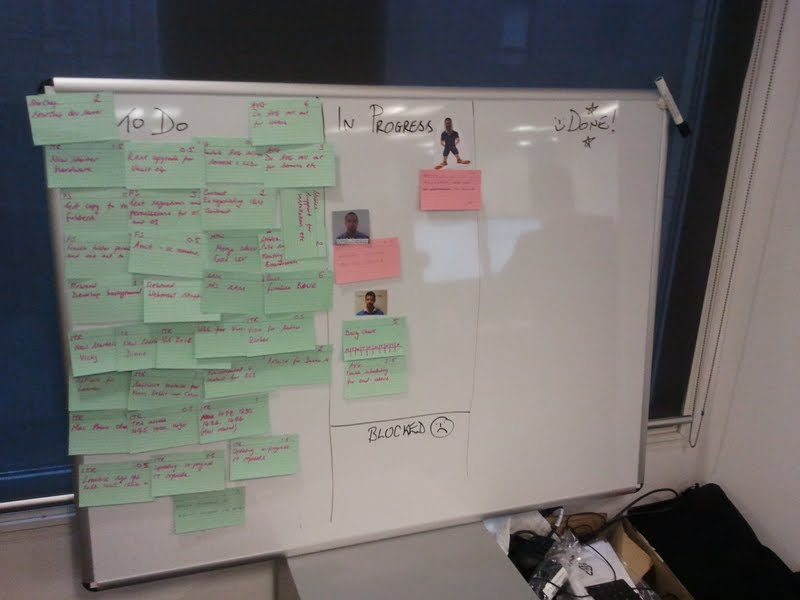

Today we started day 1 of our first ever ITOps sprint. This all came about because we needed a way of working out our productivity on “project tasks”, as well as learning how to triage our interruptions a bit better. None of the IT Ops team had tried any form of agile before, so there’s a mix of excitement and apprehension at the moment! I’ve opted for the old skool cards and sprint board (we’re using scrum by the way – more on this in a bit) rather than using an IT based system like Jira. This is mainly because everyone’s co-located, but also because I think it’s a good way to advertise what we’re doing within the office, and it’s an easy way to introduce a team to scrum.

The team already had a backlog of projects, so it was quite an easy job to break these down into cards. First of all we prioritised the projects and then sized up a bunch of tasks. We’re guessing, for this first sprint, that we’ll probably be around 40% to 50% productive on these project tasks, while the rest of our time will be taken up by interruptions (IT requests, responding to inquiries, dealing with unexpected issues etc).

Sprint 1 – planned, or “committed” tasks are on green cards, while interruptions go on those lovely pinky-reddish ones.

I’m using a points system which is roughly equivalent to 1 point = 1 hour’s effort. This is a bit more granular than you might expect in a dev sprint, but since we’re dealing with a very high number of smaller tasks, I’ve opted for this slightly more granular scale.

As well as project work, there was also an existing list of IT requests which were in the queue waiting to be done. I wanted to “commit” to getting some of these done, so we planned them in to the sprint. I had originally thought of setting a goal of reducing the IT request queue by 30 tickets, and having that as a card, but I decided against this because I don’t feel it really represents a single task in it’s own right. I might change my mind about this at a later date though! So instead of doing that, we just chose the highest priority IT requests, and then arranged them by logical groupings (for instance, 3 IT requests to rebuild laptops would be grouped together). At the end of our planning session we had committed to achieving approximately 40% productivity.

Managing Interruptions

We expect at least 50% of our time to be taken up by interruptions – this is based on a best-guess estimate, and will be refined from one sprint to the next as we progress on our agile journey. Whenever we get an interruption, let’s say someone comes over and says his laptop is broken, or we get an email saying a printer has mysteriously stopped working, then we scribble down a very brief summary of this issue on a red/pink card and make a quick call on whether it’s a higher priority that our current “in progress” tasks. If it is, then it goes straight into “in progress”, and we might have to move something out of “in progress” if the interruption means we need to park it for a while. Otherwise, the interruption will go in the backlog or in the “to do” list, depending on urgency.

At the end of the sprint we’re expecting to see a whole lot more red cards than green ones in the “Done” column. Indeed, we’re only a couple of hours into the first sprint an already the interruption cards contribute more than a 4:1 ratio in terms of hours actually worked today!

Interruptions already outweigh “committed” tasks by 4:1 in terms of hours worked – looks like my 40% guess was a bit optimistic!

Triage and Priorities

One of the goals of this agile style of working is to get us to think a bit smarter when it comes to prioritising interruptions. It’s been felt in the past that interruptions always get given higher priority over our project work, when perhaps they shouldn’t have been. I suspect that in reality there’s a combination of reasons why the interruptions got done over project work: they’re usually smaller tasks, someone is usually telling you it’s urgent, it’s nice to help people out, and sometimes it’s not very easy to tell someone that you aren’t going to do their request because it’s not high enough priority. By writing the interruptions down on a card, and being able to look at the board and see a list of tasks we have committed to deliver, I’m hoping that we will be able to make better judgement calls on the priority, and also make it easier to show people that their requests are competing with a large number of other tasks which we’ve promised to get done.

Why Scrum?

I don’t actually see this as the perfect solution by any means, and as you might be able to tell already, there’s a slight leaning towards Kanban. I eventually want to go full-kanban, so to speak, but I feel that our scrum based approach provides a much easier introduction to agile concepts. Kanban seems to be much more geared towards an Ops style environment, with it’s continuous additions of tasks to the backlog and its rolling process. I think the pull based system and the focus on “Work In Progress” will provide some good tools for the ITOps team to manage their work flow. For now though, they’re getting down with a bit of scrum to get used to the terms and the ideas, and to understand what the hell the devs are talking about!

Retrospectives, burn-downs and Continuous Improvement

We’ll stick with scrum for a while and at the end of our sprint we’ll demo what project work we actually got through, as well as advertise the amount of IT requests we did, and the number of “interruptions” we successfully handled (although I don’t think I’ll keep calling them “interruptions” :-)). I’m also looking forward to our first retrospective, which we’ll be doing at the end of each sprint as a learning task – we want to see what we did well and what we did badly, as well as take a good look at our original estimations!

I’ll keep track of our burndown, and as the weeks go by I’ll try to give the team as much supporting metrics/information as I can, such as the number of hours since an interruption, the number of project tasks that are stuck in “In Progress” etc. But most important of all, we’re looking at this as a learning experience, an opportunity for us to improve the way we manage projects and a chance for everyone to get better at prioritising and estimating.

I’ll keep the posts coming whenever I get the chance!